Electronic medical records (EMRs) – software systems where physicians, nurses, and other healthcare workers store, retrieve, and act on clinical data – are fundamentally broken. This sentiment is so widely shared among healthcare workers that it has become almost trite to point it out. Patients feel it too – we’ve lost count of the number of times we’ve heard “isn’t it in my chart?” when we ask a question during a clinical visit.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of EMRs do not facilitate storing, retrieving, or acting on information in an efficient or intuitive way. The most broken element of most charts is the free-text segments – where clinicians store narrative text data about the patient’s medical concerns, their own diagnostic impressions, and their treatment plans.

Free-text segments are critical both to pass information forward into the future and to collaboratively manage information across a team of generalists and specialists in different roles. It’s not possible to store all of that information in your head anymore, even if it was feasible 50 years ago (which is also doubtful). It’s a disservice to patients to imagine that we could. So we need a good electronic system to help. There are many ways a clever system designer could build software to organize free-text data for a single patient – data about multiple medical topics, collaboratively stored, retrieved, and used by numerous healthcare professionals, evolving over the course of years. An ideal system would, at a bare minimum, make it easy to store and organize information intuitively, such that it would be quick to retrieve relevant data later.

The specific way that most clinicians and EMR companies (in America, at least – we can’t speak to anywhere else) have chosen to organize this data is empirically terrible. It’s terrible because clinicians hate using it. It’s terrible because you can’t find relevant information quickly because charts are riddled with useless, out-of-date, and erroneous information, scattered across hundreds of different documents. The information which is both relevant and correct requires herculean effort to find. Clearly, the EMR is failing at its most basic job. Beasley et al elucidated a great framework for this ‘information chaos’ over 10 years ago, and it’s still accurate.

In our study, we used the information chaos framework: particularly, the two hazards described in the Beasley paper as “information overload” and “information scatter”. We examined a corpus of >100 million free-text notes written by thousands of different healthcare workers at our hospitals and clinics to quantify information overload and scatter. Information overload is pretty easy to quantify. We just counted the total free-text data in the corpus; this was ~32 billion words, eight times the size of the English Wikipedia at the time we checked. It was astonishing to us that a single academic healthcare system in one city in one country over 6 years produced eight times more free-text data than the global resource dedicated to capturing all of the human knowledge worth knowing. Not all of that information is relevant to a particular doctor visit or hospital admission, to be sure, but a clinician is still responsible for knowing the subset of the information that is relevant. To do that, you need a system that facilitates finding the relevant information among the irrelevant noise. The more noise there is, the more infeasible this gets and the more acutely healthcare workers feel the pain of a badly designed system.

Speaking of noise, we next looked at a subset of information overload well-known to clinicians – duplicate information. This is information that is already in a patient chart, but for whatever reason a clinician sees fit to repeat it again in a separate text document in the same chart (in clinical parlance, each individual document is called a “note”). We found that just over 50% of words were duplicated, that this fraction has been increasing over the past 6 years, and that this phenomenon is ubiquitous across all patients, clinicians, and healthcare worker types. That means 16 billion words have been duplicated over the past 6 years in just one health system. Many clinicians who reached out to us were surprised that the fraction was so low – predicting that 70% or more would be duplicated. This staggering statistic illustrates the degree to which the current free-text information management paradigm is broken. It should be a call to action – to deeply revamp documentation to save patients from medical error and clinicians from information management burnout.

“Now, wait a second!” some clinicians might be saying. “Sometimes information stays the same, so it makes sense to re-document it!” For instance, if a patient has a cough on July 3rd when they see you in the clinic, and they still have the same cough on July 12th, maybe you re-write (or more likely, copy and paste) the phrase “patient has a productive cough” in the July 12th note. Of note, information gets duplicated both across time (from past notes into future notes) and across teams (from one doctor or nurse’s note to another). Doesn’t it make sense that if information stays the same over time, you should re-document it?

Well, it would make sense if you take for granted everything about the underlying documentation paradigm, which you certainly shouldn’t. The obvious responses by anyone familiar with modern word processing software outside of a healthcare context are “(1) Why do you have to make a new text document every time you see the patient? Can’t you just edit the old document and track changes?” and “(2) Why does every healthcare worker have to maintain their own separate set of text documents? This sure sounds like a lot of wasted effort finding and collating information from other people’s notes. Can’t they just collaborate on a single shared document?” It’s hard to argue with these points. Sure, we all know colleagues who still send around multiple versions of word documents with convoluted names like “prospectus_020122_jsedits_v2_finaledits_060220” when collaborating, but we can likely all agree that collaborative documentation systems like Wikipedia or Google Docs provide much better software paradigms for collaborative editing of a text document which evolves over time. There’s absolutely no principled reason we can’t have a similar model in clinical documentation systems.

We believe that what we call the “note paradigm”is a key cause of massive amounts of duplication. The “note paradigm” is simply the two assumptions contested in the above paragraph: (1) that every new patient encounter requires a new document, and (2) that every healthcare worker must create their own documents. When a phenomenon is as ubiquitous and predictable as duplication, we can’t blame it on individual clinicians being “lazy” or even individual EMR vendors designing slow software or overwhelming user interfaces. The problem is deeper than the EMR level. It’s at the paradigm level, which underlies the assumptions about how documentation is done, how documentation systems should be built, and how medical care is regulated by the government and billed by insurance companies. It’s taught in medical schools that you have to write a “progress note” every time you see a patient, and that different specialists have to write their own “progress notes”. At this point, the note paradigm is the water we swim in; it becomes hard for many to even recognize that it is a specific design choice, or that it could be otherwise.

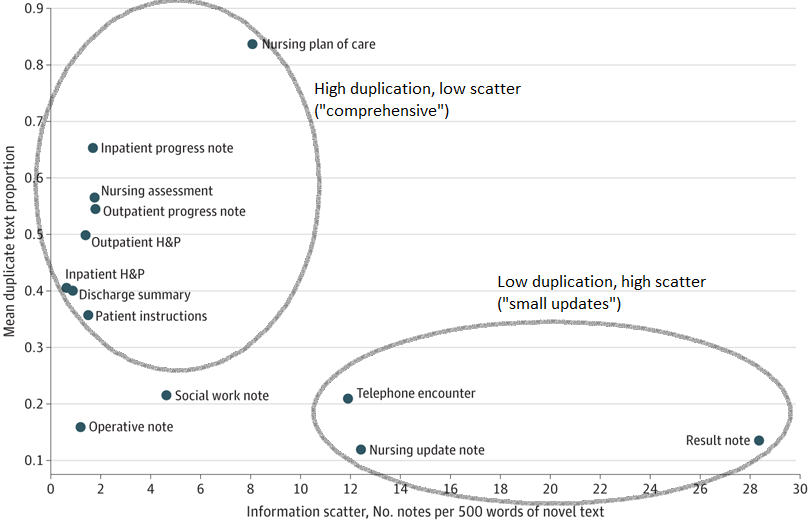

It’s easy to see how the note paradigm leads to information overload if you think about documentation incentives. Imagine a primary care clinician responsible for a patient with 5 different medical problems, all of which require adjustment of medications and 3-month check-ins. In this situation (assuming no eidetic memory), every 3 months, the clinician will need to remind themselves of all the relevant information about those problems, gather new information, incorporate it into decision-making, and document the new current state of the patient’s medical problems after the visit. Under the current paradigm, their choices are either (1) to use each of their notes as a complete and comprehensive state-of-the-patient, adding new information each time but keeping all of the old information around, or (2) just document the changes from the last visit to this visit in each note. Choice (1) leads to high information duplication as old information is persisted in every new note, but low scatter because all the relevant information is in the most recent document. High duplication increases textual errors as out-of-date information is perpetuated without change. On the other hand, choice (2) leads to shorter notes, low duplication, and high scatter because the information is now only contained in the entire set of notes, not just the most recent. High scatter necessarily increases the time needed to collate and synthesize the relevant text as all notes would need to be reviewed at every encounter to get the full story.

So without implementing a collaborative documentation system, there will remain an extremely strong trade-off between duplication and scatter and this will play out differently depending on the author’s role in a patient’s care. In particular, we’d expect that healthcare workers who treat patients’ medical problems over time (primary care doctors, psychiatrists, or specialists) would prefer to minimize scatter at the cost of high duplication. Extra work is done upfront to collate information so it can be copied forward and persistently available with minimal work. On the other hand, healthcare workers who treat patients’ problems temporarily (urgent care doctors, surgeons, nurses answering triage phone lines) would have no incentive to collate information and so would write brief notes that capture the problem at hand at the cost of high scatter. The real loser in these situations is the patient, who would be better treated if the long-term care team knew about the short-term problems, and the short-term care team had all the relevant context of the patient’s long-term care plan.

This trade-off is exactly what we empirically see when we plot scatter vs. duplication for different note types in our study. Some note types have high duplication and low scatter, exemplified by physician progress notes which aim to summarize the entire current ‘state of the patient’. These notes are comprehensive (low scatter) but duplicate lots of past information. Other note types have high scatter and low duplication, exemplified by note types that document a single isolated event e.g. (“result” notes, which comment on the results of a particular lab test; or telephone encounter notes, which document a short phone call with a patient). Very few note types have both high duplication and high scatter, except for those that are almost entirely auto-generated boilerplate text. From this picture (and our own clinical experiences), we can infer that clinicians often duplicate text because the highly scattered alternative would be worse.

The electronic medical documentation system is broken and causing clinician burnout. It affects every patient and clinician, regardless of their medical problems or clinical role, and it should be taken seriously. If we want to fix the problem, we need to properly identify and label it. The software wrappers – the systems we use every day – are only a symptom of the real problem, the note paradigm and the underlying assumptions about documentation. Individual rules to “ban” or “limit” duplication provide a solution for a different problem, not for remedying the root cause of duplication. To address that, we have to understand the motivation, which is clearly to minimize scatter, and so any limitation on duplication has to be paired with a non-duplicative tool for decreasing scatter or increasing information density per screen. Acknowledging these problems is easy. Fixing them on the other hand, will require deep cultural changes in medical training and practice, as well as changes in the billing practices, governmental regulations, and legal requirements surrounding medical documentation. But what better way to answer the question, “Isn’t it in my chart?”, than “You’re right! It’s right here.”

About Subha Airan Javia, MD

Subha Airan Javia, MD, FAMIA, is the CEO of CareAlign, a clinical workflow management technology company. She is also a hospitalist at Penn Medicine.

About Jackson Steinkamp, MD

Jackson Steinkamp, MD, is an internal medicine resident at Penn Medicine with a degree from Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine at Boston University.