PCCI’s Vulnerability Index: Uncovering and capturing factors in Dallas’ COVID-19 risk

Taking the fight to COVID-19

Management of pandemic spread (e.g., COVID-19) has tested the healthcare, political, and social fabric of communities around the world. For all, the term “flatten the curve” has come to represent how specific measures, such as social distancing, can slow the spread of the virus, which in turn can help to mitigate the tidal surge that would overwhelm the capacity of the healthcare system. For any region, there is a critical window of opportunity to leverage advanced analytics, geospatial modeling (hot-spotting), and integrated patient-management tools to better equip civic leaders and care delivery teams with real-time information to mitigate the surge and save more lives. Until treatments and vaccines are available, daily life will continue to be impacted by this disease which continues to reveal symptoms even after initial infections are no longer critical.

Building Firehouses

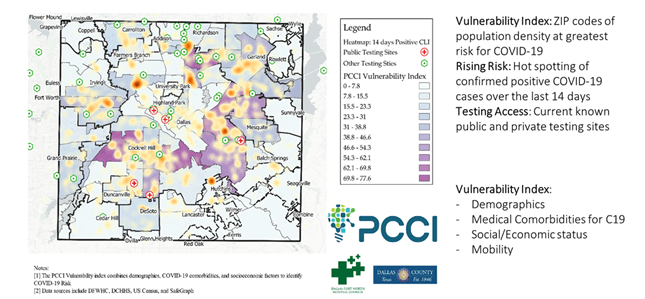

We at PCCI focus on using data science and clinical expertise to improve health for vulnerable populations. We developed the Vulnerability Index as a way to assist community and healthcare leaders to address the factors that cause COVID-19’s exponential spread. By analyzing the geospatial distribution of COVID-19 risk factors PCCI is able to identify communities especially at risk for COVID-19, allowing for targeted community support and intervention.

The analogy to consider is fire prevention. Emergency management has both long term considerations (where to locate a firehouse) as well as short term considerations (identifying active fires). Similarly, COVID-19 risk has long-term factors and short-term considerations.

Some of these factors are infeasible to address in a short-term manner. Where people live who have known COVID-19 comorbidities, like diabetes and similar, typically won’t change in the near future. Similarly, where communities facing poverty and similar socioeconomic distress are located, won’t change due to COVID-19’s presence. Finally, the demographics of a community, such as the number of people who are elderly, won’t change in a short timescale. As each of these are known factors for COVID-19 risk, we incorporate these into the Vulnerability Index.

However, simply because a risk factor is connected to COVID-19, that does not mean that the risk factor causes COVID-19. As an example, consider a community’s socioeconomic distress. Socioeconomic distress does not directly cause COVID-19, but rather people facing hard economic times may have fewer options to adhere to public health recommendations, such as staying at home, reducing social contact, working from home, and similar. This presents an intervention opportunity for public health and community leaders — by addressing a community’s ability to lock down, through increased testing and disease identification sites, rent or mortgage moratoriums, food distribution, utility forgiveness, and other basic needs assistance, community leaders can decouple a community’s COVID-19 risk from economic distress.

Putting out fires

By addressing long term factors, PCCI’s Vulnerability Index opens the door for a community to understand its local inherent risk. The next question is where to put resources right now. Their emerging risk is where the current COVID-19 cases are and where current patients tend to work, play, worship, and live. Incorporating anonymous, aggregated mobility data and recent COVID-19 hotspot information identify where urgent attention is necessary. Culturally appropriate media messaging via radio, television, and targeted social media, community-based focus messaging, canvassing, and contract-tracing starting points such as places of worship, barbershops, grocery stores, etc., pop-up testing site location decisioning, and similar public health actions can be prioritized by understanding which communities have the most urgent need.

Building the Vulnerability Index

We set out to build an index that comprehensively captures the social, clinical, and public health complexity of COVID-19. In addition, the index would have to be evidence-based, equitable, practical, and actionable, for ease of use by local community and public health leaders.

Our assessment used correlation analysis (both rank and Pearson) to analyze COVID-19 positive cases and COVID-19 like illnesses, as tracked by local emergency rooms admission, at a ZIP code level. We assessed using several weighting approaches: raw, population density weighting, population density normalization (which identifies the relative burden of disease), and percent of the population. Compellingly, the results were directionally similar across all weighting approaches and highly correlated in three of the weighting approaches.

Per the CDC, older age–typically ≥65 years old–and a set of comorbidities–including diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), autoimmune disease, certain cancers, chronic kidney disease, heart disease, obesity, and respiratory disease–are associated with the risk for COVID-19 severity. We collected US Census demographic data and anonymized clinical and demographic data from Dallas patients from a large regional data set, the Dallas Fort Worth Hospital Council Foundation, that gathers data from over 70 local and regional hospitals on hospital and emergency room utilization. The image below shows the distribution of patients with at least one known COVID-19 comorbidity.

COVID-19 Comorbidity Patient Distribution

The CDC also recommends social distancing as a key prevention step for COVID-19 spread, implying that communities unable to implement social distancing or stay-at-home measures are at higher risk for COVID-19 infection. To address this we built a social risk construct based on changes in community mobility in response to stay-at-home orders, or lack thereof. We used data from SafeGraph to measure changes in mobility from a baseline in February 2020 (pre-pandemic mobility) to May 2020 (pandemic mobility under stay-at-home restrictions). We defined lockdown adherence as a continuous variable that increases as people’s mobility decreases under lockdown measures. We found an 81% correlation between areas that are able to lock down and areas that have higher social deprivation.

Social distancing in Dallas County: lockdown adherence (top) versus area deprivation (bottom, pop. weighted by census blockgroup). Scatterplot on the right.

Finally, the association between low socioeconomic status and the prevalence of chronic health conditions (including COVID-19-related comorbidities) is well documented. We used the Area Deprivation Index (ADI)), a 17-item composite metric of social deprivation from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, as a measure of neighborhood social risk. We also examined racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 risk and its overlap with social deprivation.

We built the PCCI Vulnerability Index to be multi-dimensional, incorporating social, clinical, and demographic risk factors, to capture both the individual impact of each risk factor and synergies among risk factors.

To test the robustness of our conceptual assumptions and ensure the PCCI Vulnerability Index is evidence-based, we collected data on COVID-19 positive case rates in Dallas County and COVID-19-like illness symptoms (CLI) from Parkland Hospital, that we used to check the validity of the hypothesized association between the PCCI Vulnerability Index or its subcomponents and COVID-19 cases or CLI. It was important to include CLI as a validity check because it is less marred by testing bias than COVID-19 case rates, and therefore provides an additional robustness check for our assumptions. The evidence is compelling: the PCCI Vulnerability Index has a stronger correlation to a community’s COVID-19 initial pandemic experience than any of the individual risk factors.

Rank correlations of PCCI VI and factors to COVID-19. Pearson correlations followed a similar pattern.

Finally, we examined whether there were racial/ethnic disparities in COVID-19 risk and, if so, what were potential drivers of such disparities. This step is essential as it provides insights into the racial/ethnic/ cultural composition of vulnerable populations as well as actionable risk factors to drive tailored, culturally adapted interventions. At the same time, by capturing elements of racial/ethnic disparities, the PCCI Vulnerability index strives to drive equity in COVID-19 -related community interventions.

The PCCI Vulnerability Index has Strong Validity for Capturing COVID-19 Risk

The PCCI Vulnerability Index is strongly associated with the risk for COVID-19 infection in a community. The higher the index, the higher the risk of COVID-19 infection. Although all risk factors (comorbidities, age, social deprivation, and mobility) are strongly correlated with COVID-19 infection, the PCCI Vulnerability has the strongest association with COVID-19 risk, resulting from the index’s ability to capture each risk factor’s individual effect as well as synergies across risk factors.

The PCCI Vulnerability Index versus COVID-19 illnesses by ZIP code.

Racial and Ethnic disparities exist in COVID-19 risk and are closely aligned with social deprivation, as measured by the ADI. Hispanic and African American neighborhoods are at the highest risk for COVID-19.

Mobility, or lack of adherence to lockdown measures, is also closely aligned with social deprivation during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. This association is likely a reflection of people’s inability to lockdown due to the types of work represented in socially deprived communities, primarily client-facing jobs or jobs performed in overcrowded conditions (such as a grocery store worker or food plant worker). Not only can they not work from home, but these workers also lack economic resilience such that they might not be able to afford to miss a paycheck.

They, therefore, are more likely to need to continue to move across the community even under lockdown measures, increasing their personal and community risk for COVID-19 exposure. As the pandemic evolves and new features occur, we expect to see novel drivers of lack of lockdown adherence, including people having “cabin fever” and electing to resume normal social activity. It is important to continue monitoring and updating the impact of community mobility on COVID-19 risk.

Takeaways

The PCCI Vulnerability Index is robust and highly correlated with COVID-19 incidence, more so than its individual components. The amount of patients in a ZIP code that has a known COVID-19 comorbidity is the strongest sub-component of the index.

Further, major differences between race and ethnic groups in a community’s experience with COVID-19 appear to be strongly related to socioeconomic deprivation.

Mobility and socioeconomic deprivation are highly correlated and a potential target for community and public health interventions. Socioeconomic factors affecting mobility may include crowded living conditions, type, and industry of work (especially client-facing jobs or crowded work environments).

Practical Uses of the PCCI Vulnerability Index

The purpose of the PCCI Vulnerability Index is to give decision-makers information identifying their communities most in need. By identifying long-term risk factors, civic and public health leaders can determine efficient, culturally aware, targeted community interventions. These interventions will necessarily impact a region’s experience with a COVID-19 outbreak; and so, the PCCI Vulnerability Index methodology can be dynamically adapted to short-term, urgent factors as well by considering both short term population mobility behavior as well as recent disease incidence.

Examples of using the Vulnerability Index may include

· School administrators and civic leaders determining local community risk and inputs to mitigation strategies

· Regional public health authorities planning fixed and mobile testing locations and hours, or community interventions targeting social determinants of health

· Health system planning and strategy to determine delayed care mitigation

· Educating community residents in areas facing elevated risk factors

About Park Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI)

PCCI is an advanced, nonprofit healthcare analytics R&D organization with a collaborative team of expert data scientists and knowledgeable healthcare professionals that go beyond analyzing a patient’s medical data to provide all-encompassing insights that are revolutionizing healthcare.