A recent article by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker describes the level of preparedness at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, as it encountered the first case of Ebola to be diagnosed in the U.S. The emergency department was as prepared as anyplace, and had rehearsed the scenarios, and reviewed the CDC checklist for Ebola preparedness. They had asked about fever in people who had traveled from the region of West Africa beset by Ebola, per the protocol. In fact, the triage nurse in the emergency department had flagged the medical chart that this was a patient for whom there was concern for Ebola.

What is most concerning is that the initial triage screening, which raised the alert, was not fully communicated to the rest of the care team. The emergency department physician – overwhelmed by volume as emergency department physicians are – did not realize the patient had traveled from Liberia, and sent the patient home, suspecting a much more common viral gastroenteritis. The patient was home for two days, potentially exposing others, before returning for admission and treatment. Sadly, the patient subsequently died from the disease.

The subsequent public health response, isolating all the potential contacts and monitoring them for the 21 day incubation period to ensure no further spread, will contain this particular incident.

Of broader concern is the frequent, routine breakdown of information exchange between different parts of the medical system. In fact, it has been well documented that failure to communicate “known” critical information is the most common cause of major medical errors. With the current spread of Ebola, such failure takes on a much more dangerous and ominous role.

Where are we with rapid clinical information exchange?

The tools in place in most institutions are based on in-house Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems. EHRs are generally cumbersome, and are focused on gathering information in-house, and are used as much for securing payment as for documenting clinical information. A testament to the cumbersome nature of EHRs, especially in a busy emergency department setting, is the fact that many emergency departments employ scribes to follow the clinician around and create the record in the EHR, freeing the clinician to move on to the next patient.

EHRs are not particularly good for rapid information sharing between care team members either, which is why the use of SMS text messaging (albeit a non-HIPAA compliant behavior) is common.

HIPAA compliant mobile tools for sharing information about patients, and embedding that information into a longitudinal patient timeline, is a technology that is emerging currently. This has not been an easy thing to build, and requires some difficult back-end pieces to work together in order to be successful:

(1) rigorous identity management of providers and patients, so that the data gets put in the right place

(2) a flexible and robust data schema that can accommodate all the different kinds of EHR data (as well as device and consumer data) in a single structure

(3) a social chart around a patient, showing the connections with the care team, which is the basis of managing consent and information sharing permissions.

How would a critical incident be handled differently with the right tools?

In the Ebola case, where the right questions were asked because of good emergency department preparedness and protocols, the key is sharing that information with the care team. The reality is that the information needs to be real-time, quickly accessible, and used by everyone delivering care. Lightweight messaging about patients in the triage queue can be sent to all the emergency department care team members, bypassing the cumbersome EHR interface.

What if a care setting is not as prepared as the hospital in Dallas? Like a doctor’s office, urgent care center, or pharmacy-based ready-clinic? Use of an adjunctive Patient Check-In app could be leveraged quite well, where the important questions, such as recent travel and current fever or other gastrointestinal symptoms, can be asked. This can be filled out by a triage nurse, or (on tablets implemented in a clinical office) by patients themselves. If there is a flag raised by the answer to these checklist questions, that automatically becomes a part of the longitudinal record, and appears immediately for other care team members to be alerted.

The Critical Role of Health IT

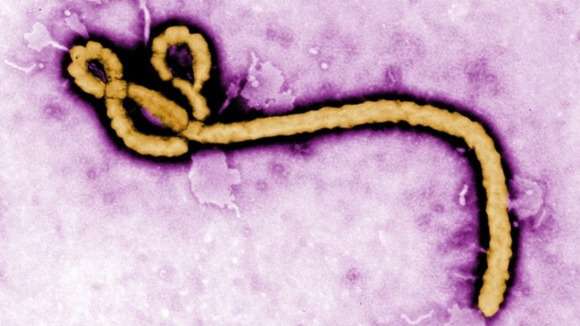

Ebola won’t be beaten simply by care coordination tools. The eventual response will need to be based on therapeutics and preventives (such as immunization) – these have yet to emerge, though rigorous work is being done here. Supportive treatment helps, but the disease still carries about a 70% mortality rate.

However, in the current state of response to Ebola, contagion containment is the key. It involves collaboration between different points of care (emergency departments, perhaps clinics and doctor’s offices as initial potential contact places in the future) and public health agencies. It involves reaching out to potentially exposed people, regardless of where they are. Quick, responsive health IT tools play a key role in this effort. No single EHR system, given that they are built as tools for in-house use within a given institution, will be sufficient – the workflows go beyond the walls of any institution.

The setting is frightening. Ebola can be contained, if the information sharing is good. The newly-emergent technologies just now coming onto the marketplace may prove to be invaluable tools which can help in this far-reaching effort.

Dr. Robert Rowley is the Co-Founder and Chief Medical Officer of Flow Health, a next generation communication platform for care teams and patients, facilitating transitions of care, and aggregating patient-centered data from all the sources where it is found. From its inception through 2012, Dr. Rowley had been Practice Fusion’s Chief Medical Officer, having created the underlying technology in his own practice, and using that as the original foundation of the Practice Fusion web-based EHR.