What You Should Know:

– New analysis of Texas hospital price data reveals a transparency paradox: discounted cash prices for common services are often significantly lower than the rates hospitals negotiated with commercial insurers, according to a new research study from Trilliant Health.

– For diagnostic colonoscopies, the median cash price was 32% below the median negotiated rate. This disconnect means that employees on high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) and the employers who sponsor them are likely subsidizing unnecessary healthcare costs.

The Market Paradox: When Being Insured Costs More

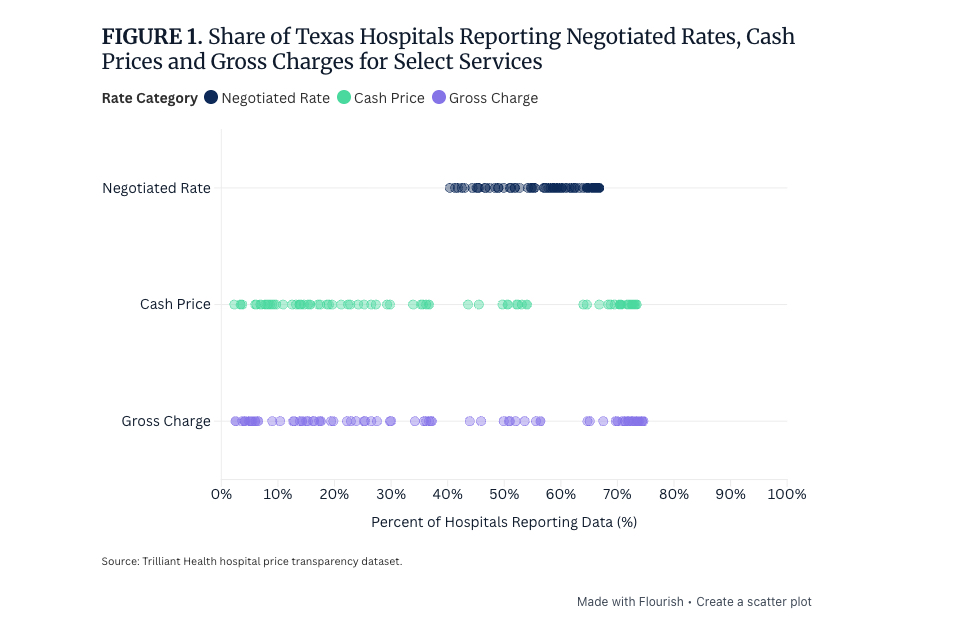

The federal Hospital Price Transparency rule, effective since 2021, mandated that hospitals publish both their discounted cash prices and the rates negotiated with insurance companies. The intention was to increase price awareness and potentially bend the rising healthcare cost curve.

However, the practical reality unearthed by analyzing this public data is striking: for four out of five common services analyzed across 327 Texas hospitals, discounted cash prices were lower than the negotiated rates secured by commercial insurers.

This finding creates a fundamental market paradox:

- For HDHP Members: Until a patient meets their annual deductible, they are responsible for the entire cost of the service up to that threshold. If the cash price is lower than the negotiated rate, that insured patient pays more than an uninsured patient would, despite paying insurance premiums.

- The Diagnostic Colonoscopy Example: For CPT 45378 (diagnostic colonoscopy), the median cash price was $1,554, which is 32% below the median negotiated rate of $2,275.

The only exception found among the sampled services was the sleep study (CPT 95810), where the negotiated median rate ($1,473) was lower than the cash price median ($4,644).

The Barriers to Decision Utility

While the data is now theoretically available, it is functionally useless to the typical patient or employer. This disconnect between data availability and decision utility is rooted in several systemic issues:

- Lack of Incentive: Commercially insured patients are almost never responsible for the full negotiated rate and have little incentive to focus on the total cost of services.

- The Emergency Default: Approximately 50% of all hospital admissions originate in the emergency department (ED). Due to EMTALA, hospitals cannot inquire about a patient’s ability to pay, meaning the default mindset for maximizing revenue for inpatient services is to maximize billing to health insurers.

- The Cognitive Burden: Even for truly “shoppable” services, the complexity of understanding how deductibles, copays, coinsurance, and out-of-pocket maximums interact with both cash and negotiated rates creates cognitive barriers that prevent informed decision-making.

As a result, hospitals rarely volunteer cash alternatives, and few patients know or inquire about them.

Implications for Employers and the Health Economy

The consequences of this price disconnect extend far beyond the individual patient with an HDHP.

- Employer Subsidies: Even after an insured patient hits their deductible, the employer who sponsors the group health plan continues bearing the financial burden of inflated negotiated rates. When an employer’s supposed “group negotiating power” yields rates higher than what an uninsured cash-paying patient would pay, those employers are effectively subsidizing unnecessary healthcare costs.

- Value Erosion: The study highlights the extreme price variation for the same service at the same hospital. Negotiated rates for a diagnostic colonoscopy varied by 24x across health plans. This means the same hospital can provide high value in one network and low value in another, making the value of a commercial insurance benefit highly erratic.

- The Revenue Cycle Mindset: The default assumption for revenue cycle management in hospitals is insurance utilization, as uninsured patients represent only a minor portion of hospital revenue. This ingrained mindset prevents the disclosure of beneficial cash alternatives at the point of care.

For price transparency to maximize its value, policymakers, hospitals, and employers must close the gap between data existence and decision-making utility. Until comparative pricing information reaches patients and employers before they need to choose a provider network—not after the fact, like pricing in an airport retail shop—transparency regulations will remain a theoretical tool rather than a practical solution for bending the healthcare cost curve.