Lots of financial scrambling, but the numbers still don’t add up

Is healthcare a business?

In the United States, the question has been asked time and again but never satisfactorily answered. By virtue of publically financed healthcare systems, the rest of the developed world has decided, to a greater or lesser extent, that medicine and healthcare are not pure businesses—that citizens have a right to care, even when they can’t pay all associated costs.

It’s starting to look like Americans won’t be able to duck the question for much longer.

In the last year, the profitability of U.S. hospitals eroded for the first time since the Great Recession, pushing some closer to and others over the solvency precipice. Revenues are down and costs are up. And these issues appear systemic and entrenched, giving rise to a series of important and relevant questions: How can hospitals adapt? If they do, will they still survive? And, do we as a nation think it’s important to make hospitals accessible, even if they lose money?

As recently reported in the New York Times, analysis by Moody’s Investors Service shows that this year nonprofit hospitals had their worst financial performance since the Great Recession. Among the 383 hospitals studied, revenue growth dipped from a 7 percent average to 3.9 percent on declining admissions. For the last two years, expenses have grown faster than revenues, and fully one quarter of all hospitals are operating at a loss.

In a word, Moody’s describes the situation as “unsustainable” because it is the product of what look like enduring realities:

- Private insurers did not increase payments to hospitals.

- Medicare reduced payments due to federal budget cuts.

- Demand for inpatient services declined as outpatient care options rose.

- Retail outpatient options now compete with hospital clinics.

- Patients with higher copays and deductibles chose not to seek care.

- Hospitals are buying up physician practices.

- The costs of electronic medical record systems are impacting the bottom line.

Will all these influencers remain constant? No. But they don’t have to. A handful should be enough to push some hospitals into the next life.

The Moody’s analysis is simply evidence of continuing weakness in the healthcare marketplace. Earlier this year Standard & Poor’s evaluated 138 healthcare systems and found an operating margin of 2.2 percent for 2013, down from 2.9 percent in both 2012 and 2011. Standalone hospitals were squeezed slightly more than hospital systems because they have a narrower range of operations and services from which to profit.

While the decrease might be the point, can we pause for a moment to recognize the paltry 2.9 percent margin? Just a tremor in the operating budget of any hospital with that small a margin will probably send it over the financial cliff.

In Sebastopol, California, north of San Francisco, 37-bed Palm Drive Hospital is shutting its doors. Despite clear demand for both inpatient and outpatient care, Palm Drive has labored for years to make up for reductions in Medicare reimbursement rates with more inpatient services. Over the next ten years across California, hospitals will see a reduction of more than $23 billion in payments, including $17 billion related to prevention and readmission penalties instituted by the Affordable Care Act.

“Unfortunately, Palm Drive is not an isolated case,” said Jan Emerson-Shea, a spokesperson for the California Hospital Association. “There are hospitals across the state that are really struggling to remain open and operating.”

Indeed, nationwide the outlook for smaller, rural and standalone hospitals is gloomy. Moody’s sees more earth-shaking change coming when insurers move to pay for quality and not services—from a system that thrives on illness to one that rewards health and wellness. The transition is happening now, and the pace will only increase.

The knee-jerk reaction to this situation for any organization with a budget is to lower costs. For hospitals, that means reducing staff and further burdening existing employees. This may be an effective strategy in accounting or restaurants, but the result in won’t be late nights poring over spreadsheets or cold entrees. Labor reductions in healthcare can only decrease quality and increase costs in the long run. More errors lead to less reimbursement, and the squeeze continues until the hospital gives up the ghost.

There is a way out of the squeeze, however, available to those that can adapt by lowering costs and increasing quality. Hokey as it may sound, it is possible to redefine hospitals for a future based on best practices.

Where does this supposedly mythical future exist even now?

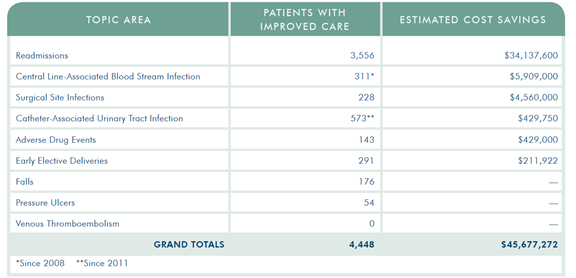

How about in Wisconsin? Members of the Wisconsin Hospital Association have used quality improvement programs to decrease readmissions, lower infection rates and curtail adverse drug events, resulting in statewide savings greater than $45 million over several years. As President Steve Brenton wrote in WHA’s 2013 Quality Report:

Health care value can be improved by either raising quality while controlling costs, or by decreasing cost while maintaining quality. If value improves, patients, payers, providers and suppliers can all benefit while the economic sustainability of the health care system increases. When improvement work reduces hospital-associated infections and readmissions, the improvements in quality translate to cost savings, and that is a value to local employers, insurers and patients.

The WHA Partners for Patients program targets best practices and outcomes based on Institute for Health Care Improvement programs. Organized efforts across member hospitals have achieved these remarkable outcomes and savings.

Of course, these results require health IT and electronic health records for programs that create outcomes stakeholders value and will pay for. Hospitals must promote their quality metrics and negotiate rates with these stakeholders.

But, while the numbers from Wisconsin and other regions are encouraging, this is not simply a situation of making the numbers work. The savings realized when hospitals focus on quality are in the tens of millions; the reductions in payments expected to continue are in the billions. There is a yawning chasm between the two.

Currently, payers are moving to a 5/1 ratio. A survey released last month by Blue Cross/Blue Shield estimated that for every $5 in reimbursements, only $1 was a reward for improving care and lowering costs. As these and similar arrangements are negotiated, you can be certain that the smaller non-profit hospitals are last in line.

The mandate for quality care and cost savings is clear, but the numbers still don’t add up. Can non-profit hospitals change fast enough? Until they do, or if they can’t, are we as a society willing to support them because we think the care should be available?

Edmund Billings, MD, is chief medical officer of Medsphere Systems Corporation, the solution provider for the OpenVista electronic health record.