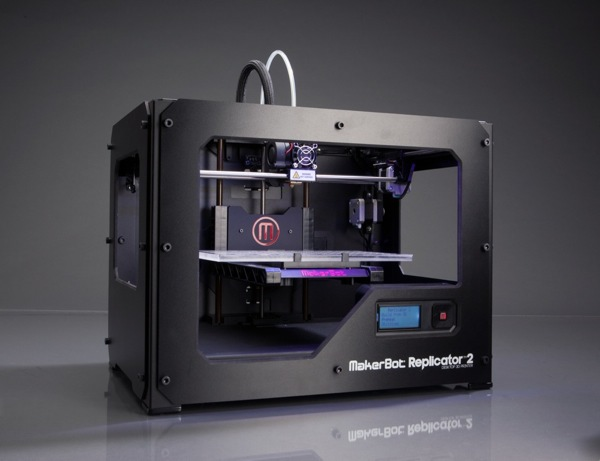

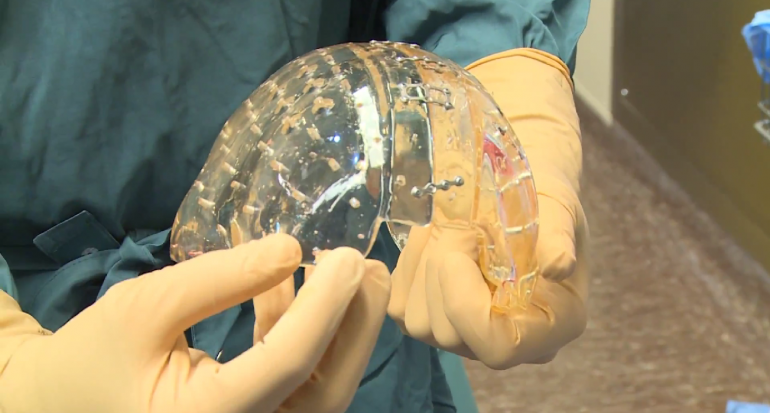

What is 3D printing? Traditionally, 3D printers have worked by additive manufacturing, a process in which a machine layers materials, such as plastic or glass, to create an object. This kind of printing is common to places like Boeing, Honeywell and General Electric, where many parts are manufactured with 3D printing. In the world of healthcare, 3D printing is already used to create dental implants, hearing aids, contact lenses and prosthesis that are tailored to the individual. Creating customized medical devices offers many advantages for the patient. The perfect fit of a prosthetic limb, for example, makes it much more comfortable to wear and reduces the risk of infection or other complications. Replacing a knee or hip with a device that is customized for that particular patient can cut down on operating time and expenses, promote faster healing and possibly lead to a more comfortable, longer-lasting joint. There is also a psychological aspect to the use of 3D printed parts. “Because 3D printed designs can be unique and cool, things like prosthesis that used to be something to hide are now a fashion statement,” said Sarah Boisvert, the chief 3D printing officer at Potomac Photonics, Inc. “Bespoke and 3D Systems are demonstrating this today with customers matching their artificial legs to their outfits. The social ramifications are even more powerful than the technical.” Early successes with 3D printing The victories for 3D printing are already piling up. Top medical facilities like the Mayo Clinic are now offering flexible replacement knee joints printed with nylon, which mimic bones and cartilage. Cornell University is busy printing experimental heart valves and bone implants, while researchers at Wake Forest University have been successful in creating kidney cells. The reach of 3D printing has improved and even saved lives. In 2011, a man in the UK who lost half his pelvis to bone cancer received a new pelvis created of 3D materials, and is still happy with the results. In 2012, infant Kaiba Gionfriddo made headlines when doctors in Ohio implanted a 3D printed airway splint that allowed him to breathe normally. The child is now a healthy toddler. In March 2014, it was reported that 75 percent of an American patient’s skull was replaced by a 3D implant created by Oxford Performance Materials. Made of a biomedical polymer, the artificial skull was created to exact specifications for the patient, and included surface details that encouraged easy attachment and new cell growth. But the wonders of 3D printing aren’t limited to implants. In February 2014, doctors at Kosair Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky. needed to operate on a small child with multiple heart defects. By printing a 3D version of the child’s heart, doctors could study the heart’s defects and create a surgical plan before wheeling the child into the operating room. The surgery was a success. Just announced last week, a 22 year old woman’s skull was successfully replaced with a 3D-printed implant. Performed by Dr. Bon Verwejj of University Medical Center (UMC) Utrecht, the skull was 3D-modeled and then printed as a single full piece slotted and secured into place. 3D printing can ensure the components of the skull are an exact fit. Verwejj stated, “this has major advantages, not only cosmetically but also because patients often have better brain function compared with the old method.”  The future of 3D printing in healthcare As the advantages of 3D printing become clear, many hospitals and physicians are embracing what it can do. In 2013, there was a $1.2 billion market for 3D printing in healthcare; by 2018, that will increase to over $4 billion, according to a study by Visiongain. While much of that booming market might come from the increased use of customized prosthesis and other devices, there are much more ambitious 3D printing uses on the horizon. One of these advances is known as bioprinting, or the ability to print living tissues. The printers make use of “bio-ink,” a blend of living cells. The bioprinter builds a structure from these cells, layer by layer, to create human tissue. Researchers are already testing the technology for use in creating skin grafts, knee cartilage and small heart valves. The next step? Creating organs for the human body. The ability to create a kidney, pancreas, or heart from a person’s own cells with a bioprinter has enormous implications for healthcare, including reducing the lengthy transplant lists, improving the chances of recovery and possibly even controlling or curing chronic diseases, like diabetes. “Printing body parts from cells or tissue is years off as initial results are just in, and we would still have to go through FDA approvals,” Boisvert said. “But the ability to have a perfect match and not have to wait for a donor would save countless lives and is the future of medicine. Organs made from tissue, not plastic or metal, would perform more like those with which we are born.” 3D printing is already making a significant impact, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. “Printing organs made from cells is really in the early stages but initial results are promising,” Boisvert said. “I expect this sector to hit the market in ten to twenty years, and then the impact will be huge.”

The future of 3D printing in healthcare As the advantages of 3D printing become clear, many hospitals and physicians are embracing what it can do. In 2013, there was a $1.2 billion market for 3D printing in healthcare; by 2018, that will increase to over $4 billion, according to a study by Visiongain. While much of that booming market might come from the increased use of customized prosthesis and other devices, there are much more ambitious 3D printing uses on the horizon. One of these advances is known as bioprinting, or the ability to print living tissues. The printers make use of “bio-ink,” a blend of living cells. The bioprinter builds a structure from these cells, layer by layer, to create human tissue. Researchers are already testing the technology for use in creating skin grafts, knee cartilage and small heart valves. The next step? Creating organs for the human body. The ability to create a kidney, pancreas, or heart from a person’s own cells with a bioprinter has enormous implications for healthcare, including reducing the lengthy transplant lists, improving the chances of recovery and possibly even controlling or curing chronic diseases, like diabetes. “Printing body parts from cells or tissue is years off as initial results are just in, and we would still have to go through FDA approvals,” Boisvert said. “But the ability to have a perfect match and not have to wait for a donor would save countless lives and is the future of medicine. Organs made from tissue, not plastic or metal, would perform more like those with which we are born.” 3D printing is already making a significant impact, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. “Printing organs made from cells is really in the early stages but initial results are promising,” Boisvert said. “I expect this sector to hit the market in ten to twenty years, and then the impact will be huge.”