Getting a new credit card number is relatively easy, but you can’t get a new genome.

In October 2023, 23andMe experienced a data breach resulting from a credential stuffing attack. In this cyberattack, hackers exploit reused usernames and passwords obtained from previous data leaks to gain unauthorized access to user accounts. Initially, approximately 14,000 accounts were compromised. It exposed the sensitive personal and genetic data of about 5.5 million users and an additional 1.4 million profiles.

A hacker group called “Golem ” stole the most intimate personal data of 23andMe’s subscribers, including full names, profile photos, birth years, locations, family surnames, grandparents’ birthplaces, ethnicity estimates, highly specific genetic information, and other personal details that users had opted to share. The data was freely available in large text files to anyone who knew where to look on the dark web.

To understand the implications of this attack, we’ll need to look back just a bit. Revolutionizing Personal Data Access

The genetic testing company 23andMe was one of the first companies to allow “normal people” to gain insight into the secrets held in their genomes. Virtually overnight, using some of the most advanced technology at the time, people could see genetic traits ranging from eye color to disease predisposition. Like many advances, personalized access to sensitive genetic data preceded serious conversations about those data’s risks. 23andMe successfully provided the world access to some of the most sensitive personal data (our genomes) well before we could fully understand the security and privacy implications.

While life sciences firms are incredibly advanced in their application of technology, they are not an industry known for their leadership in cybersecurity. The pace of research or the pressure to get to market with a new product often outpaces the security implications, and much of the actual security and compliance work is done after the fact. Large corporations and the largest academic institutions have budgets to protect themselves and study compliance implications, such as GDPR and HIPAA, before a new technology is brought to market. Smaller biotech firms on the cutting edge often can’t afford or don’t budget for these steps, placing their resource more around getting their product out.

Fast innovation, sensitive intellectual property, and evolving regulations all work together to drive the severity of this situation. Despite handling some of the most valuable data in the world—ranging from proprietary drug formulas to patient records—many life sciences firms still lag in cybersecurity maturity.

According to recent industry intelligence:

• Cybercriminals aggressively target biotech and pharmaceutical companies for intellectual property theft, extortion, and espionage.

• Supply chain risk is a growing concern, as many life sciences firms rely on third-party research, storage, and cloud infrastructure, each adding a layer of vulnerability.

• Identity-based attacks are surging, fueled by weak credential management and a lack of identity governance—a gap highlighted by IBM’s X-Force report, which noted that cloud account credentials now make up 90% of cloud-related assets sold on the dark web.

Life sciences organizations are custodians of highly sensitive data—intellectual property, clinical trial results, genetic information, and patient records. At the same time, these organizations are subject to less uniform enforcement than healthcare providers. Healthcare organizations dealing directly with PHI are subject to aggressive HIPAA enforcement by the OCR (Office for Civil Rights), with breaches leading to significant fines and mandated corrective action plans. Life sciences companies often straddle the line between research and care delivery and tend towards their research and development roots.

My Time in Life Sciences

As the Chief Information Officer for the biotechnology firm Integrated DNA Technology (IDT) for over twenty years, I was reminded of these risks daily. Our technology team ensured that the digital systems behind ordering, producing, and delivering synthetic DNA and RNA worked securely and reliably. Our firm supported over 80,000 clients in academic and corporate life sciences. From the biggest pharma companies to the smallest research labs, our products gave us visibility into the entire life sciences industry.

We faced cyber threats from activist groups and nation-state actors alike. Anonymous has publicly stated its opposition to Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) and frequently attacked customers. Many of our researchers had close ties to their research facilities in China, some of whom competed directly against our clients.

Deep Dive – 23andMe’s Breach Data

We needed to analyze what was taken from 23andMe to understand the attack’s methods and impact. Cybersecurity firms are often asked to research the implications of these attacks and the exfiltrated breach data. Closely analyzing the data sold by the hackers helps us protect both the individual client and the overall industry affected. For example, a credit card breach from a single gas station may impact several financial institutions that initially issued those cards. Forensic investigation of credit card files provides valuable insights to diagnose the source of the issue and prevent future breaches.

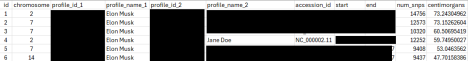

An example of data from the 23andMe breach posted on the Dark Web.

Analysis of the 23andMe breach data uncovered some unlikely attack victims – including Elon Musk. While there is no way to confirm that this is Elon Musk’s data without an actual genetic sample, he’s referenced in several areas of the breach. If these are his data, Elon is as much a victim of this breach as I am. (Yes, 23andMe has my personal data as well.)

The breach contained a project that looked to be a project comparing Elon Musk’s private information to that of over a thousand individuals. This research looked at several patterns of genetic regions within specific chromosomes for various pieces of highly sensitive information. These data provide insights into predisposition to disease and unique human traits, such as brain development and metabolism.

In the example above, a search was leaked comparing Elon Musk by comparing regions of his second, seventh, and fourteenth chromosomes with several thousand other people in the 23andMe data. The matches (redacted) are listed as profile_name_2 and include the specific areas studied. Centimorgans (cM) is a measure of genetic complementarity, and the higher the number, the greater the match. For

reference, an identical twin would share 100% of their DNA, resulting in a 3,600-3,800 centimorgan score. The match with the first profile is most consistent with a distant familial relationship (like 3rd–4th cousins, or even more distant if from an endogamous population like Ashkenazi Jews or Amish). It’s not close enough for half-siblings, first cousins, or even 2nd cousins—those would typically share multiple segments totaling 200–800+ cM.

The results of an extraordinarily detailed and personal comparison of Elon Musk’s genome were available online. Hackers could potentially use this data for any number of illicit activities, including blackmail, research exploitation, discrimination, and social manipulation.

Due to the scope of this cybersecurity breach, 23andMe filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on March 23, 2025, and in conjunction with the bankruptcy filing, co-founder and CEO Anne Wojcicki resigned. The company plans to pursue a court-supervised sale of its assets to maximize business value. Whether the data becomes available to a threat actor via the breach or a future breach of the company acquiring 23andMe’s assets (the data), the cat is out of the bag. Once genetic data is disseminated, it’s impossible to control the use of the information.

Complicated Problems, Simpler Solutions

The unfortunate demise of 23andMe is a canary in the coal mine. The life sciences industry must commit to protecting these data. This is best accomplished in 2025 by mastering the fundamentals—the core building blocks of cybersecurity hygiene. These aren’t glamorous, but they are extraordinarily effective. Most breaches today are caused by basic missteps: weak passwords, unpatched systems, and poorly configured access controls. Life sciences firms can prevent nearly all but the most advanced nation-state-level attacks by focusing on fundamentals.

Identity and access management (IAM) is a solid first step in life sciences to develop more effective cybersecurity hygiene. This means ensuring that every user has only the necessary access—and nothing more. Implementing strong authentication methods like multi-factor authentication (MFA) and adopting least-privilege access models prevents bad actors from exploiting stolen or weak credentials, which remain among the top causes of breaches, according to the Verizon Data Breach Investigation Report and IBM X-Force reports.

Second, patch and vulnerability management must be operationalized. Most exploited vulnerabilities are known and patchable. Life sciences organizations must establish a routine cadence to identify, prioritize, and remediate these weaknesses. Even better, they could automate it. This is where governance comes in—connect patch management to accountability, making it a tracked KPI at both the IT and executive levels.

Next, third-party and supply chain security is especially critical in the life sciences industry, where R&D and data handling often involve complex webs of CROs, labs, and digital platforms. Life sciences organizations should perform due diligence on partners, demand security attestations (like SOC 2 or HITRUST), and restrict third-party access through segmentation and zero trust principles.

To integrate these fundamentals into organizational governance, life sciences firms should:

• Elevate cybersecurity at the board and executive levels as a standing agenda item. • Appoint a strong Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) or virtual CISO to oversee strategy and implementation.

• Embed cybersecurity into product development lifecycles—especially for firms developing digital health tools or platforms.

• Invest in ongoing employee cybersecurity awareness and training, focusing on real-world phishing simulations and data handling policies.

• Align with frameworks like NIST CSF, HITRUST, or ISO 27001 to ensure consistency and audit readiness.

The government can also create uniform expectations and drive the adoption of best practices through regulation, incentives, and by sharing threat intelligence. Unfortunately, industries that are self-regulated don’t have that threat of enforcement from agencies like the OCR, so they tend to ignore the risks and gamble on the chance that they won’t have a breach.

In Summary

The 23andMe breach is a wake-up call for consumers and the entire life sciences industry. It underscores what many of us have known for years: cybersecurity isn’t a technical checkbox—it’s a fundamental pillar of trust. Life science organizations must rise to the challenge as stewards of some of the most sensitive data. The tools are available. The expertise exists. What’s needed now is leadership.

In an era where our DNA can be digitized, stored, and stolen, protecting the data must become as important as collecting it. The future of personalized medicine isn’t just about scientific breakthroughs—it’s about preserving the Trust that makes those breakthroughs possible.

About Aaron R. Warner, CEO of ProCirucular

Aaron R. Warner is the founder and CEO of ProCircular, an information Security and Privacy firm focusing on midsized businesses. A former CIO and CTO of Integrated DNA Technology, he’s spent more than two decades working in IT and InfoSec. Mr. Warner is a Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) and certified Securiity+ engineer, and a full member of the FBI/DHS Infragard partnership.